A Gutsy Approach to Human Hormones

Gabriela Arp, a Ph.D. candidate in UMD’s Biological Sciences Graduate Program, says our gut microbiomes house hormone transformers with the power to change our bodies and brains.

There was a time not long ago that we gave the human gut little thought in the big picture of human health; it was the place where food is digested, and gassy emissions are produced, full stop.

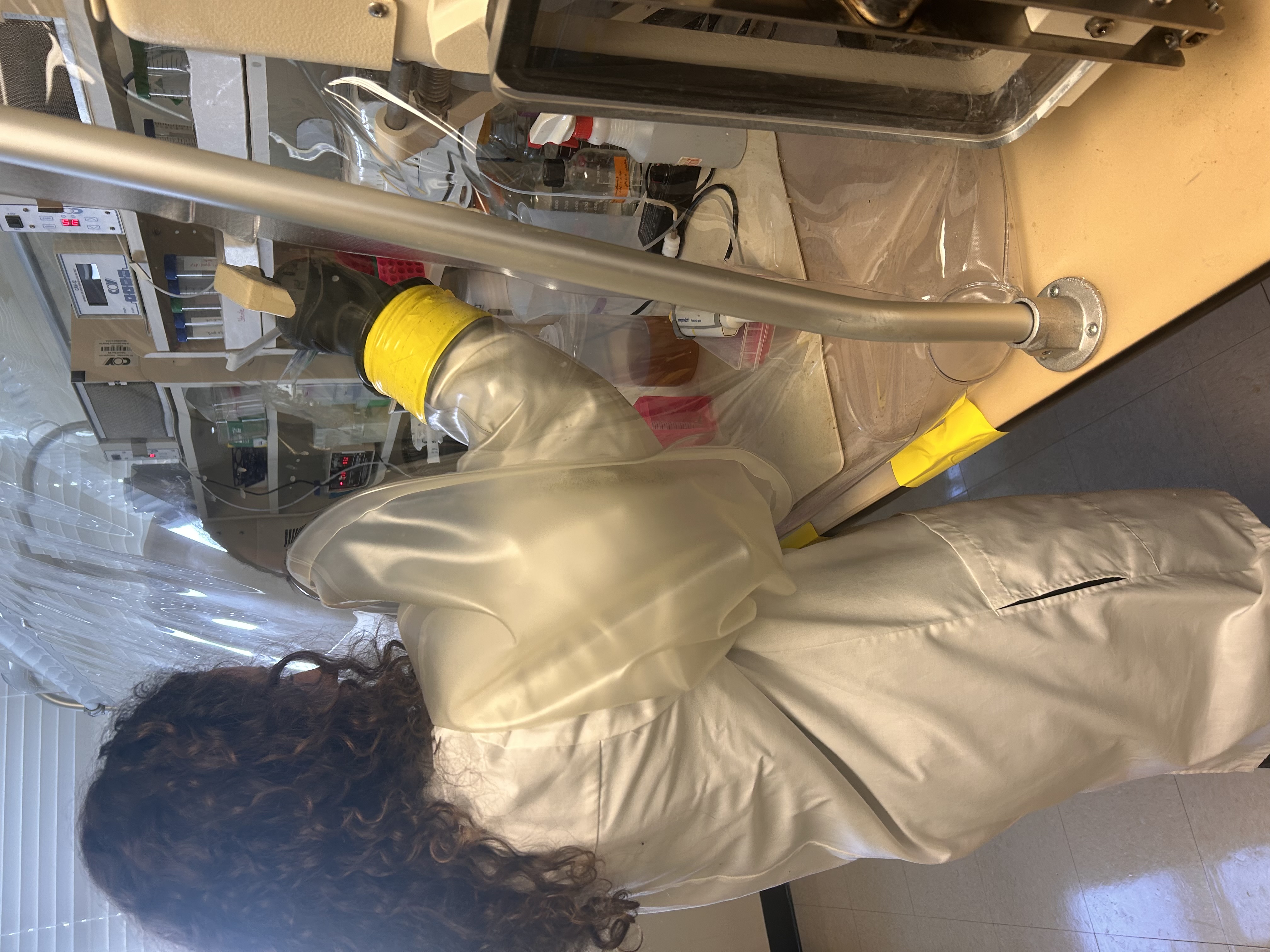

No longer. Now, scientists like Gabriela Arp, a Ph.D. student in Assistant Professor Brantley Hall’s lab in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology at the University of Maryland, are picking through the bacteria in the gut’s vast microbiome to learn more about just how crucial these bacteria are to our digestive system, and also how the activity in the gut microbiome may affect our brains, moods, hearts and hormones.

“It is an active organ whose microbial members appear to be involved across our bodily systems,” Arp said. “What is compelling is how important our gut bacteria may be and objectively how little we know about them.”

So many microbes, so many mysteries

The human microbiome consists of trillions of microbes—including bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea, and eukaryotes; scientists call it the “second human genome” and now consider it a separate organ, as it has its own metabolic and immune activity. Our guts house 10 times more microbial cells, some 100 trillion of them, than the rest of our body’s germ populations combined, with about 5,000 species represented. Identifying these organisms and figuring out what they do “is like categorizing an ecosystem that is constantly changing,” Arp said.

Working in Hall’s lab with help from graduate student Angela Jiang on the computational side, Arp is doing her part: She’s identifying and characterizing gut bacterial enzymes and has already discovered that these enzymes affect steroid hormones like progesterone, cortisol and testosterone.

“Hormone health, especially in women, has been vastly understudied, and I see gut bacteria as a unique way to approach it,” Arp said. As steroid hormones help regulate reproduction, menstrual cycles, stress, brain function and immune responses, “we need to know how gut microbes affect these hormones’ structure and biological activity.”

Traditionally, steroid hormones were thought to be controlled mainly by our organs, but Arp is uncovering bacterial enzymes that glom onto human hormones and can chemically transform them.

“That these enzymes exist and do what they do solidifies that the gut microbiome is an active participant in human endocrine biology, capable of activating, inactivating, or regulating hormone signaling through bacterial enzymatic pathways,” Arp said. “This challenges previous models of hormone regulation primarily focused on endocrine glands and the liver.”

Arp has kept busy with multiple projects since she began her Ph.D. work in 2022. In her investigation of the gut bacterium Clostridium, she discovered that gut bacteria can specifically target human hormones.

“And synthetic hormones aren’t immune,” noted Arp, “which means gut microbes may, for example, reduce the effectiveness of birth control and explain why only a fraction of the hormone is absorbed by the body and why women are prescribed really high doses.”

Following her gut

Long before she became a scientist, Arp’s most powerful influence was her father, a physicist; as a child Arp remembers being wide-eyed sitting in his office.

“The textbooks were stacked floor to ceiling, Star Wars figurines on the shelf, and then over in the lab, all these machines—microscopes, magnets, lasers,” she recalled. “From early on I knew I wanted some version of that life. That meant a career in science.”

After graduating from UMD in 2019, with degrees in public health and Spanish Arp spent nearly three years doing a postbaccalaureate research fellowship at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

“That experience solidified it all for me,” she said. “In the lab at NIH every day looks different, you’re constantly learning, and you are challenged in a rewarding way. And here at UMD I’ve never gotten the ‘Sunday Scaries’—I like coming to work, even on Mondays! I fundamentally enjoy what I do.”

Now, as Arp sees the growing public interest in gut health, and that urgency to find the “next big thing” that will ensure health and longevity, she worries about unscientific fads that seem to get eaten up by the mainstream media and the public.

“In this area there is a lot of room for misinformation; people want magic bullets and we don’t have them,” Arp said. “For now, there’s still substantial mechanistic research to do to try to tease out well-supported biological effects from overstated claims. I hope my work can be part of finding the truth.”